Archeologists have said that the early human Australopithecus sediba, discovered in 2008 in South Africa, likely ate a diverse diet of bark, nuts leaves and other plant products.

But now, a new study in the journal Nature Communications has revealed the teeth and jaw composition of A. sediba may have caused the primate to dislocate its jaw if it tried to eat particularly hard foods.

"Most australopiths had amazing adaptations in their jaws, teeth and faces that allowed them to process foods that were difficult to chew or crack open. Among other things, they were able to efficiently bite down on foods with very high forces," David Strait, an anthropologist from Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement.

is a smallish pre-human species that lived around two million years ago. Showing up in the fossil record about four million years ago, the larger group of australopiths featured some human traits, such as the ability to walk on two legs. However, these creatures lacked the large brain, small jaws and flat face of modern humans.

A. sediba

"Australopithecus sediba is thought by some researchers to lie near the ancestry of Homo, the group to which our species belongs yet we find that A. sediba had an important limitation on its ability to bite powerfully; if it had bitten as hard as possible on its molar teeth using the full force of its chewing muscles, it would have dislocated its jaw,” said co-author Justin Ledogar, a researcher at the University of New England in Australia.

Testing jaws likes vehicles

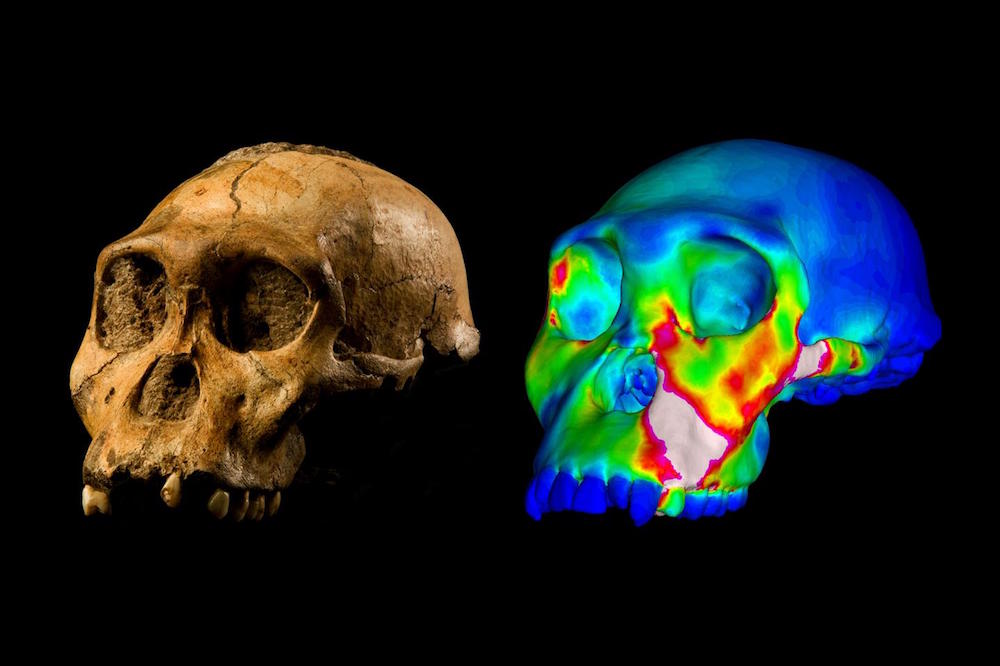

In the study, researchers conducted biomechanical testing of a computer model based on a fossil skull discovered in 2008. The biomechanical techniques the team used are also used by engineers to test the structural integrity of vehicles, machine parts and other mechanical devices.

"These unexpected, but clearly intriguing, findings of the study are substantiated by the team of scientists having spent over a decade conducting meticulous, thorough experimental research on chewing mechanics in order to validate this application of computer-assisted modeling," said Kristian Carlson, an evolutionary studies researcher from the University of the Witwatersrand. "This collaborative research effort underscores the crucial scientific benefits that South African scientists enjoy as a result of the formal association between South Africa's Department of Science and Technology and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France."